Long-time followers of this blog may have noted that I don't post as often as I did during 2009, my first year of blogging. There are a couple of reasons for this.

First, once I set about writing my dissertation in 2010, I would spend entire days writing, so it became difficult also to take the time to write blog posts. Now that I am working, I still find it hard to post more than 2-3 times a month, but I will continue to post here when I identify issues that deserve more analysis than is provided in the mainstream media.

Secondly, my increased use of Facebook allows me to make shorter commentaries on news stories that don't necessarily merit a longer blog post. If this is something that also interests you, please "like" the Facebook page for my book, Designated Drivers, which you can find here.*

On that page I comment mostly on China's auto industry, but also on general business/government issues in China. Also, please feel free to jump in and comment as well, either here or on the Facebook page. This is all about making each other smarter, so I welcome comments and criticism.

_______________________

* Sorry, but I really hate the term "like" that Facebook insists on using. If you prefer, think of it as "following" instead. You can be interested in what I have to say without necessarily liking it. :)

Thursday, March 29, 2012

Wednesday, March 28, 2012

Is GM handing China another win?

General Motors announced today that it has signed a memorandum of understanding with the China Automotive Technology and Research Center (CATARC) in which CATARC will reportedly...

Since part of GM's purpose is to gain influence over policymakers, this relationship with an organization that is part of the central government cannot hurt. But there is more to CATARC than meets the eye.

Not only is CATARC an auto industry regulator that is essentially owned by the central government, but it is also a competitor of GM's through its ownership in the Tianjin Qingyuan Electric Vehicle Company (Qingyuan). According to Qingyuan's website, the company both develops and produces clean energy vehicles and components, which sounds remarkably like something that GM does.

Qingyuan's "principal shareholder" is CATARC, and another of Qingyuan's shareholders is the Tianjin Lishen Battery Company, a producer of lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles, which is, of course a competitor of LG Chem, the manufacturer of the battery in the Chevrolet Volt. (Lishen, incidentally, makes the li-ion battery for the Coda electric car.)

So what does all of this mean? Am I saying that GM has handed its intellectual property over to CATARC so they may copy at will? Not exactly. CATARC, after all, also has a reputation to protect, so I am doubtful that they would so blatantly copy GM's Volt technology. But how certain can GM be that its technology will not find its way, through CATARC, into the hands of Qingyuan, or Lishen, or any of the dozens of Chinese automakers who bring their cars to CATARC for testing?

GM is no stranger to having its IP copied in China. Back in 2003, GM discovered that Chery had somehow obtained the plans to the Chevrolet Spark, and used them to develop the QQ which Chery got to market several months ahead of the Spark. And when GM went to its partner, Shanghai Auto, to complain about this miscreant that had been copying its technology, only then did GM learn that Shanghai Auto was also a part owner of Chery. (Long story short, GM sued, then settled out of court with Chery, which admitted no wrongdoing, and Shanghai Auto got rid of its shares in Chery.)

In all honesty, I find it hard to blame Chinese automakers for copying foreign technology and designs. After all, this is what all developing countries do when they are trying to catch up. All developed countries -- including the US -- at one time or another, copied other countries' technologies with reckless abandon.

I do, however, blame foreign automakers (and manufacturers in pretty much any industry) for sometimes naively risking their shareholders' valuable IP for a share of the Chinese market. The goal of the Chinese automakers is to win -- as it should be. But foreign automakers need to understand that the ultimate goal of China's automakers is to no longer need them. When Chinese partners say their aim is for a "win-win," this means they get to win twice.*

___________________

* I don't know for certain whether I was the first person to say this about the concept of "win-win", but I had not heard it before I tweeted it from my hotel room in Shanghai in January of 2010 (as documented by @rudenoon on his blog). :)

...manage GM’s fleet of demonstration Volts and will assist GM China in meeting certain objectives.Who is CATARC? From their English website:

These [objectives] will include gaining the support of key decision makers crafting vehicle electrification policy in China.

China Automotive Technology and Research Center (CATARC) was established in 1985 response to the need of the state for the management of auto industry and upon the approval of the China National Science and Technology Commission. It is now affiliated to SASAC.CATARC is "affiliated to SASAC" (State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission) which is essentially the organization that holds the shares of central state-owned enterprises. CATARC is also a major regulatory organization in that all automobiles need to be tested by CATARC before they may be certified for the road in China.

As a technical administration body in the auto industry and a technical support organization to the governmental authorities, CATARC assists the government in such activities as auto standard and technical regulation formulating, product certification testing, quality system certification, industry planning and policy research, information service and common technology research.

Since part of GM's purpose is to gain influence over policymakers, this relationship with an organization that is part of the central government cannot hurt. But there is more to CATARC than meets the eye.

Not only is CATARC an auto industry regulator that is essentially owned by the central government, but it is also a competitor of GM's through its ownership in the Tianjin Qingyuan Electric Vehicle Company (Qingyuan). According to Qingyuan's website, the company both develops and produces clean energy vehicles and components, which sounds remarkably like something that GM does.

Qingyuan's "principal shareholder" is CATARC, and another of Qingyuan's shareholders is the Tianjin Lishen Battery Company, a producer of lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles, which is, of course a competitor of LG Chem, the manufacturer of the battery in the Chevrolet Volt. (Lishen, incidentally, makes the li-ion battery for the Coda electric car.)

So what does all of this mean? Am I saying that GM has handed its intellectual property over to CATARC so they may copy at will? Not exactly. CATARC, after all, also has a reputation to protect, so I am doubtful that they would so blatantly copy GM's Volt technology. But how certain can GM be that its technology will not find its way, through CATARC, into the hands of Qingyuan, or Lishen, or any of the dozens of Chinese automakers who bring their cars to CATARC for testing?

GM is no stranger to having its IP copied in China. Back in 2003, GM discovered that Chery had somehow obtained the plans to the Chevrolet Spark, and used them to develop the QQ which Chery got to market several months ahead of the Spark. And when GM went to its partner, Shanghai Auto, to complain about this miscreant that had been copying its technology, only then did GM learn that Shanghai Auto was also a part owner of Chery. (Long story short, GM sued, then settled out of court with Chery, which admitted no wrongdoing, and Shanghai Auto got rid of its shares in Chery.)

In all honesty, I find it hard to blame Chinese automakers for copying foreign technology and designs. After all, this is what all developing countries do when they are trying to catch up. All developed countries -- including the US -- at one time or another, copied other countries' technologies with reckless abandon.

I do, however, blame foreign automakers (and manufacturers in pretty much any industry) for sometimes naively risking their shareholders' valuable IP for a share of the Chinese market. The goal of the Chinese automakers is to win -- as it should be. But foreign automakers need to understand that the ultimate goal of China's automakers is to no longer need them. When Chinese partners say their aim is for a "win-win," this means they get to win twice.*

___________________

* I don't know for certain whether I was the first person to say this about the concept of "win-win", but I had not heard it before I tweeted it from my hotel room in Shanghai in January of 2010 (as documented by @rudenoon on his blog). :)

Friday, March 23, 2012

Time for a Shakeout in China's Auto Industry?

Yesterday China Bureau Chief of Automotive News, Yang Jian posted an interesting article (free registration reqd.) speculating as to possible consequences of a recent slowdown in auto sales in China. In the first two months of 2012, auto sales decreased four percent, year-on-year – and this comes on the heels of (for China) a rather anemic 2011 in which sales only grew about 2.5% and Chinese-branded passenger vehicles gave up nearly two percentage points in market share to the foreign brands.

In short, Yang Jian's point is that, should this drop in sales become a trend that lasts through 2012, some of the weaker players in China's auto industry could be forced into bankruptcy or possibly out of business altogether.

From the perspective of China's central government, which has been begging and pleading for this heavily fragmented industry to consolidate itself for nearly three decades, this wouldn't be such a bad thing. (Of course it would be a bad thing for the employees of those companies that went out of business.) There are still well over 100 vehicle manufacturers operating in China (compared to only 24 in the United States), and this fragmentation prevents the industry as a whole from becoming more competitive vis-à-vis the foreign automakers.

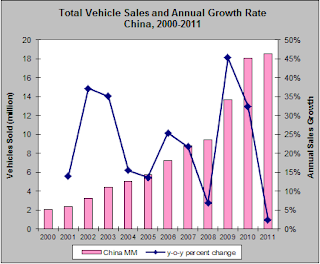

So what is the likelihood that a decline in sales could lead to a shakeout of the weaker players? Well, let's take a look at what happened the last time China's auto industry experienced a slowdown in sales growth. After enjoying annual sales growth of anywhere between 14% and 37% since 2001, the onset of the Great Recession in 2008 caused China's growth rate to drop to a horrifyingly low 7%. (Yes, the word “horrifyingly” should be interpreted sarcastically.)

I remember talking to a lot of auto industry insiders in China in the spring of 2009 when some of them lamented the fact that the much hoped-for shakeout didn't happen back then. (And it seems like Yang Jian himself may have been among those who expressed such sentiment to me then.)

Why didn't the shakeout happen?

The central government rode to the rescue with a far-reaching stimulus program that not only prevented another year of miserably low sales growth, but that, for the first time ever, launched China into position as the world's single largest market for automobiles in 2009. Hence the lamentations from some of my interviewees at the time. As Yang Jian hopes today, many of them also hoped soft sales growth would kill off some of the weaker players in 2009.

So will the central government ride to the rescue again this year?

I think it is less likely. With large cities in China already limiting the number of cars that can be sold and driven on their streets, and with the central government clamping down on overcapacity in the industry, AND now that China is already the number one auto market in the world (they can't go any higher), a rescue is probably not in the cards.

Does that mean a shakeout will occur?

I wouldn't bet on that either. Among the top-10 automakers, Chang'an, Chery and BYD each experienced sales declines in 2011, which doesn't look good for them. Except that Chang'an is among China's “Big 4” and Chery is among China's “Small 4.” What this means is that the central government has designated these automakers to be among those remaining after the industry consolidates. And BYD is privately-owned (its shares are traded in Hong Kong), and, though it hasn't sold as many EVs and hybrids as it had hoped to by now, it is probably China's best chance of having an automaker who can compete in this space.

Will a shakeout then occur among the dozens of tiny, inefficient and unprofitable automakers scattered around the country?

I think this is the best hope, but whether the downturn will be deep enough and long enough to outlast local governments' ability to prop up these firms remains to be seen. Local governments tend to be rather fond of their automakers -- even the ones that lose money.

In short, Yang Jian's point is that, should this drop in sales become a trend that lasts through 2012, some of the weaker players in China's auto industry could be forced into bankruptcy or possibly out of business altogether.

From the perspective of China's central government, which has been begging and pleading for this heavily fragmented industry to consolidate itself for nearly three decades, this wouldn't be such a bad thing. (Of course it would be a bad thing for the employees of those companies that went out of business.) There are still well over 100 vehicle manufacturers operating in China (compared to only 24 in the United States), and this fragmentation prevents the industry as a whole from becoming more competitive vis-à-vis the foreign automakers.

So what is the likelihood that a decline in sales could lead to a shakeout of the weaker players? Well, let's take a look at what happened the last time China's auto industry experienced a slowdown in sales growth. After enjoying annual sales growth of anywhere between 14% and 37% since 2001, the onset of the Great Recession in 2008 caused China's growth rate to drop to a horrifyingly low 7%. (Yes, the word “horrifyingly” should be interpreted sarcastically.)

I remember talking to a lot of auto industry insiders in China in the spring of 2009 when some of them lamented the fact that the much hoped-for shakeout didn't happen back then. (And it seems like Yang Jian himself may have been among those who expressed such sentiment to me then.)

Why didn't the shakeout happen?

The central government rode to the rescue with a far-reaching stimulus program that not only prevented another year of miserably low sales growth, but that, for the first time ever, launched China into position as the world's single largest market for automobiles in 2009. Hence the lamentations from some of my interviewees at the time. As Yang Jian hopes today, many of them also hoped soft sales growth would kill off some of the weaker players in 2009.

So will the central government ride to the rescue again this year?

I think it is less likely. With large cities in China already limiting the number of cars that can be sold and driven on their streets, and with the central government clamping down on overcapacity in the industry, AND now that China is already the number one auto market in the world (they can't go any higher), a rescue is probably not in the cards.

Does that mean a shakeout will occur?

I wouldn't bet on that either. Among the top-10 automakers, Chang'an, Chery and BYD each experienced sales declines in 2011, which doesn't look good for them. Except that Chang'an is among China's “Big 4” and Chery is among China's “Small 4.” What this means is that the central government has designated these automakers to be among those remaining after the industry consolidates. And BYD is privately-owned (its shares are traded in Hong Kong), and, though it hasn't sold as many EVs and hybrids as it had hoped to by now, it is probably China's best chance of having an automaker who can compete in this space.

Will a shakeout then occur among the dozens of tiny, inefficient and unprofitable automakers scattered around the country?

I think this is the best hope, but whether the downturn will be deep enough and long enough to outlast local governments' ability to prop up these firms remains to be seen. Local governments tend to be rather fond of their automakers -- even the ones that lose money.

Tuesday, March 20, 2012

Andrew Hupert's "Guanxi for the Busy American"

My friend Andrew Hupert, whom I first met in Shanghai several years ago, has for years managed a couple of very practical and helpful blogs on negotiating and managing in China (ChineseNegotiation.com and ChinaSolved.com). Even before I met Andrew, I always wondered why he would give away such valuable information for free.

Well, now he's finally selling part of his wisdom in an e-book entitled Guanxi for the Busy American available at Smashwords in ten different formats including Kindle, ePub and PDF. And at a price of only $2.99, it's a bit of a steal. (Seriously, Andrew, you should charge more.)

Because it's in an e-format, it's easy to keep on pretty much any device and peruse on the plane on the way to China. And whether someone is completely new to China, or an old China hand, the book is equally useful as both a source of necessary learning, or a reminder of how things work in China.

Much of this stuff simply doesn't come naturally to Westerners, and, even after nearly 20 years of travel to China, I occasionally need reminders. The book is a relatively quick and easy read -- it took me a little over an hour -- but it's packed with both theory and practice on what this mysterious guanxi thing is all about and how to navigate one's way through a potentially tricky maze of gestures and obligations.

Andrew's writing style is clean and straightforward, but also descriptive and, at times, humorous. Among the gems are statements like "Guanxi is the sweet candy shell that coats some potentially bitter medicine." What he explains is that, while the whole process of building guanxi can seem light and even fun, it is a process that the Chinese take very seriously. Mistakes made during this process can sink a partnership before it even gets off the ground.

Among the behaviors he warns against are denigrating the value of guanxi among your Chinese hosts by saying something like, "oh yeah, we have that concept in America too: it's not what you know but who you know," which is likely to be taken as an insult. Your Chinese hosts will be more flattered if you simply admit that the whole concept baffles you and that America has nothing like it. Even if that isn't true (and if you've read this book, it won't be true) it will buy you some credit with your hosts. (I mention this particular bit of advice because I know I have violated it several times in the past.)

The book also offers a way to "de-code" some of the guanxi talk you are likely to hear at an early guanxi-building session with your hosts.

One final point (among many dozens more) is that foreigners in China need to understand that their hosts generally want very much to invest in a long term relationship. But one shouldn't be fooled into thinking that a relationship that begins well will result in an eternal bond. The Chinese simply do not see it that way. The relationship will only last as long as the Chinese partner thinks he is deriving value equal to or greater than yours. Once that calculation changes, expect a re-negotiation. And if you aren't open to re-negotiation, expect your counterpart who has invested time in learning the names of your spouse, children and pets to lose interest and stop returning your calls.

The only real criticism I can think of is regarding the title. I am not so sure that North American and Western European cultures are so different that this book wouldn't be immediately useful on both sides of the Atlantic (and down under as well). Perhaps it might have been better titled Guanxi for the Busy Westerner.

Either way, people who do business in China need to load this book onto their Kindles and iPads. And if you find yourself sending a newbie to China on behalf of your company, be sure he or she has this book ahead of time. They will need to read it several times before getting on the plane, and probably several more while they are in China.

Well, now he's finally selling part of his wisdom in an e-book entitled Guanxi for the Busy American available at Smashwords in ten different formats including Kindle, ePub and PDF. And at a price of only $2.99, it's a bit of a steal. (Seriously, Andrew, you should charge more.)

Because it's in an e-format, it's easy to keep on pretty much any device and peruse on the plane on the way to China. And whether someone is completely new to China, or an old China hand, the book is equally useful as both a source of necessary learning, or a reminder of how things work in China.

Much of this stuff simply doesn't come naturally to Westerners, and, even after nearly 20 years of travel to China, I occasionally need reminders. The book is a relatively quick and easy read -- it took me a little over an hour -- but it's packed with both theory and practice on what this mysterious guanxi thing is all about and how to navigate one's way through a potentially tricky maze of gestures and obligations.

Andrew's writing style is clean and straightforward, but also descriptive and, at times, humorous. Among the gems are statements like "Guanxi is the sweet candy shell that coats some potentially bitter medicine." What he explains is that, while the whole process of building guanxi can seem light and even fun, it is a process that the Chinese take very seriously. Mistakes made during this process can sink a partnership before it even gets off the ground.

Among the behaviors he warns against are denigrating the value of guanxi among your Chinese hosts by saying something like, "oh yeah, we have that concept in America too: it's not what you know but who you know," which is likely to be taken as an insult. Your Chinese hosts will be more flattered if you simply admit that the whole concept baffles you and that America has nothing like it. Even if that isn't true (and if you've read this book, it won't be true) it will buy you some credit with your hosts. (I mention this particular bit of advice because I know I have violated it several times in the past.)

The book also offers a way to "de-code" some of the guanxi talk you are likely to hear at an early guanxi-building session with your hosts.

When they ask if you have been to China before, they want to know if you already have connections or are likely to grant them exclusive control (over your venture).And another

When they ask when you are returning to America, they want to know about your internal deadlines so they can time the negotiations to apply maximum pressure.He also offers practical advice on how to deal with endless toasts and offers of cigarettes during banquets. These are important rituals that tell the Chinese something about you. More importantly, how they react to your behavior also tells you something about what kind of partner they would be.

One final point (among many dozens more) is that foreigners in China need to understand that their hosts generally want very much to invest in a long term relationship. But one shouldn't be fooled into thinking that a relationship that begins well will result in an eternal bond. The Chinese simply do not see it that way. The relationship will only last as long as the Chinese partner thinks he is deriving value equal to or greater than yours. Once that calculation changes, expect a re-negotiation. And if you aren't open to re-negotiation, expect your counterpart who has invested time in learning the names of your spouse, children and pets to lose interest and stop returning your calls.

The only real criticism I can think of is regarding the title. I am not so sure that North American and Western European cultures are so different that this book wouldn't be immediately useful on both sides of the Atlantic (and down under as well). Perhaps it might have been better titled Guanxi for the Busy Westerner.

Either way, people who do business in China need to load this book onto their Kindles and iPads. And if you find yourself sending a newbie to China on behalf of your company, be sure he or she has this book ahead of time. They will need to read it several times before getting on the plane, and probably several more while they are in China.

Monday, March 19, 2012

Book Talk at USC

Several weeks ago I gave a talk related to my forthcoming book at the University of Southern California. Watch as I attempt to summarize four years of research and a 300-page book in less than an hour. :)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)