Today's WSJ China Realtime reports on a study by a George Mason University economist who attempts to compare corruption in the US and China. His conclusion is that corruption in America's Gilded Age (1877-1893)* was worse than corruption in China today.

Perhaps the conclusion is correct, but the methodology used by this professor is flawed. US corruption is measured by mentions of corruption in US newspapers 1870-1930. China corruption is measured by mentions of corruption in US (not Chinese!) newspapers 1990-2011.

So he is measuring corruption in two countries by the number of times the newspapers of only one of the countries mentions the word. Even if the researcher had used Chinese newspapers, the study still would have been flawed due to Communist Party control of Chinese print media throughout the period in question. (Why the author of the study did not even attempt to scan Chinese newspapers for mentions of corruption, I don't know, but I'll venture a guess that it's because he doesn't speak Chinese.)

The question the researcher is asking is a valid one. America during its Gilded Age was extremely corrupt, as is modern day China. An answer as to which one is/was more corrupt would be enlightening. It would be interesting to consider whether actions taken to curb corruption in the democratic America of the Gilded Age are even remotely applicable to modern authoritarian China.

Nice try, but we're still no closer to a valid measure for corruption that we may compare across countries.

____________________

* The official dates of the Gilded Age are considered to be 1877-1893, after which the Progressive Era began, but the author of the quoted study extends his analysis to 1930.

Thursday, December 13, 2012

Wednesday, October 17, 2012

GM and SAIC: Trouble in Paradise?

General Motors (GM) and Shanghai Auto (SAIC) announced in December of 2009 that they were deepening their partnership beyond their joint venture in China. Together they created a 50:50 joint venture, registered in Hong Kong, for expansion outside of China. Now that partnership appears to be coming apart.

Initially, the plan for the HK JV was for the two sides to work together in India and possibly elsewhere in the future. (For further insight into this particular deal, please see Chapter 4 of Designated Drivers.) As for the India venture, GM would contribute two existing factories in India, along with its Chevrolet brand, and SAIC would contribute cash -- something that GM had been seriously lacking as it had emerged from bankruptcy earlier that same year.

Another part of the deal was for GM to hand over 1% of its ownership in its 50:50 China-based JV with SAIC in exchange for about $85 million. As GM's people explained it, SAIC would be able to help GM gain bank financing outside of North America (as if no one outside the US had been aware GM was in bankruptcy).

Thanks to a clever analyst who has combed through GM's SEC filings, it has now emerged that SAIC appears to have backed out of the India joint venture, and GM has stepped in to buy out SAIC's portion for $125 million -- ironic since GM was previously so desperate that it was willing to hand over control of SAIC-GM to SAIC for a mere $85 million. The India joint venture has now gone from an equal 50:50 partnership to a 93:7 partnership in favor of GM.

One can only speculate as to why SAIC has decided to pass up an opportunity to participate in the burgeoning demand for small cars in India. Until now, the two partners, SAIC and GM, have been considered to be among the "most harmonious" Sino-foreign joint ventures.

If things have truly soured between the two partners (or if they are merely less keen on each other than they were before), SAIC has the most to lose here. In China, SAIC still makes most of its money by selling GM- (and VW-)branded vehicles. While SAIC has its "own" brands, MG and Rover, these were purchased outright from the UK and not self-developed. GM, on the other hand, appears once again to be running its massive research and development pipeline full steam ahead back at home.

Initially, the plan for the HK JV was for the two sides to work together in India and possibly elsewhere in the future. (For further insight into this particular deal, please see Chapter 4 of Designated Drivers.) As for the India venture, GM would contribute two existing factories in India, along with its Chevrolet brand, and SAIC would contribute cash -- something that GM had been seriously lacking as it had emerged from bankruptcy earlier that same year.

Thanks to a clever analyst who has combed through GM's SEC filings, it has now emerged that SAIC appears to have backed out of the India joint venture, and GM has stepped in to buy out SAIC's portion for $125 million -- ironic since GM was previously so desperate that it was willing to hand over control of SAIC-GM to SAIC for a mere $85 million. The India joint venture has now gone from an equal 50:50 partnership to a 93:7 partnership in favor of GM.

One can only speculate as to why SAIC has decided to pass up an opportunity to participate in the burgeoning demand for small cars in India. Until now, the two partners, SAIC and GM, have been considered to be among the "most harmonious" Sino-foreign joint ventures.

Now that GM has regained its profitability in North America, has GM perhaps decided it no longer needs SAIC's cash to expand to other markets? Has SAIC decided it would also prefer to go it alone?

Friday, September 14, 2012

But will China's smart, young automotive managers ever get to lead?

There is a great piece by Automotive News China Managing Editor, Yang Jian, on their site this week. (The full article is reproduced on the AdAge site here without restriction.)

Yang Jian notes that, at the recent Global Automotive Forum in Chengdu, a lot of senior auto executives couldn't be bothered to address the crowd, so they sent younger managers in their place. The result was a level of candor not normally expected of senior auto execs.

A few examples:

Yang rightly praises the pragmatism of this younger generation, and expresses hope that these younger guys will turn around the erosion of Chinese brands' market share when they get to the top. And I largely agree -- if they do get to the top, that is.

In order for that to happen, China will have to do a radical re-think of how SOEs are managed.

The way it works now is that SOE (state-owned enterprise) leaders tend to be more politician than business person. Most of them held political positions before landing in or near the head office of an SOE, and many will return to political positions after their tenures are up.

Unlike a lot of these younger managers, most of these senior managers didn't come up through the ranks in the auto industry. Even the few who may have worked in the auto industry when they were young may have possibly been just as pragmatic as today's younger managers, but something apparently changed along the way.

Leadership, unfortunately, tends to drive out a lot of idealism and replace it with survival instinct. The CEOs of state-owned enterprises work, not for a diverse group of shareholders who just want to get rich. They work for the Communist Party whose overarching goal is to remain in power -- a goal often at odds with efficient, productive and profitable business.

Yang Jian notes that, at the recent Global Automotive Forum in Chengdu, a lot of senior auto executives couldn't be bothered to address the crowd, so they sent younger managers in their place. The result was a level of candor not normally expected of senior auto execs.

A few examples:

A Chang'an VP on electric vehicles: "you will find there are still a lot of problems with these vehicles when you develop them with taxpayers' money."

Chery's sales chief admitted to short-termism: "We strived to rank first or second in sales among domestic brands,...but we forgot to ask what our future direction should be." (There are a few other examples in the original article.)

Yang rightly praises the pragmatism of this younger generation, and expresses hope that these younger guys will turn around the erosion of Chinese brands' market share when they get to the top. And I largely agree -- if they do get to the top, that is.

In order for that to happen, China will have to do a radical re-think of how SOEs are managed.

The way it works now is that SOE (state-owned enterprise) leaders tend to be more politician than business person. Most of them held political positions before landing in or near the head office of an SOE, and many will return to political positions after their tenures are up.

Unlike a lot of these younger managers, most of these senior managers didn't come up through the ranks in the auto industry. Even the few who may have worked in the auto industry when they were young may have possibly been just as pragmatic as today's younger managers, but something apparently changed along the way.

Leadership, unfortunately, tends to drive out a lot of idealism and replace it with survival instinct. The CEOs of state-owned enterprises work, not for a diverse group of shareholders who just want to get rich. They work for the Communist Party whose overarching goal is to remain in power -- a goal often at odds with efficient, productive and profitable business.

Wednesday, September 5, 2012

Fragile Bridge: Conflict Management in Chinese Business

In March of 2012, Andrew Hupert released his first e-book, Guanxi for the Busy American, a quick yet thorough read on how to navigate the potentially treacherous waters of guanxi in China. He now follows Guanxi with his second book (within less than a year!), Fragile Bridge: Conflict Management in Chinese Business.

As much as I enjoyed Guanxi for the Busy American, I found Fragile Bridge to be even more interesting and applicable across many more situations. Hupert provides the reader not just with practical advice on structuring agreements and contracts, but more importantly, he spells out the warning signs of future conflict. Many behaviors that come natural to the Western business person appear as red flags to their Chinese counterparts, and avoidance of these behaviors are a real key to setting up a partnership for success.

Even the word “conflict” in the title of this book should be an indicator of just how differently the Chinese and Western sides of a partnership approach business. Much of what counts for “conflict” in this book is indeed “conflict” from a Western perspective, but from the Chinese perspective, it is simply part of doing business. While Westerners are accustomed to a fair amount of conflict leading up to the signing of a contract, the general expectation is that this is the point at which conflict ends, and both parties do their best to adhere to the terms of the contract.

While it has now become practically cliché to say that Chinese and Westerners view contracts differently, Hupert opens a door on what the Chinese side is thinking both before and after contract signing, how they constantly assess the performance of both the business and their foreign partner, and how they will maneuver to improve the terms of the deal for themselves. Having this knowledge certainly will not prevent conflict, but understanding what motivates the Chinese side, and having Hupert's advice on how to address Chinese concerns (most of which they will never verbally express) will equip Western business people far better than an entire lifetime of experience in a Western-only business setting.

This 10-chapter book is structured to mirror the life of a Chinese-Western partnership from beginning to end – whether that end is a continuance of the partnership or a dissolution. In each chapter, Hupert provides clear theoretical explanations of how and why Chinese and Western expectations differ, and then he provides case studies that illustrate both successful and unsuccessful ways of dealing with conflict.

There is also a larger, fictional case study about an American partner, Stan, and a Chinese partner, Jimmy who meet in college in the US and establish a business together in Shanghai. Each chapter ends with a telling of the portion of the Stan & Jimmy story that applies to that chapter, and the story is so well-told, that the reader will find it hard to stop reading at the end of any given chapter. (In my case, I read the entire book on a flight from Los Angeles to Taipei in about three or four hours.)

I am not certain whether it was intended this way, but Hupert's new book seems to be a sort of prequel to his first book in that it is a longer and broader work covering many aspects of Chinese-foreign business partnerships, just one of which happens to be guanxi (which can be loosely translated as “connections” though there is much more to it than that). To anyone who has yet to read Guanxi for the Busy American, my advice would be to read Fragile Bridge first, then pick up Guanxi for a more in-depth treatment of this very important topic.

For those who have already read Guanxi, you will find that Fragile Bridge contains the same kind of practical advice, except that it is extended to many more situations in addition to the building of guanxi. And regardless of the order in which you read Andrew Hupert's two excellent books, if you're serious about succeeding in business (or any kind of negotiation) in China, you really cannot afford not to have both of these books in your e-reader.

Fragile Bridge: Conflict Management in Chinese Business is available for $9.99 in Kindle format at Amazon.com and in many other e-book formats at Smashwords.com.

As much as I enjoyed Guanxi for the Busy American, I found Fragile Bridge to be even more interesting and applicable across many more situations. Hupert provides the reader not just with practical advice on structuring agreements and contracts, but more importantly, he spells out the warning signs of future conflict. Many behaviors that come natural to the Western business person appear as red flags to their Chinese counterparts, and avoidance of these behaviors are a real key to setting up a partnership for success.

Even the word “conflict” in the title of this book should be an indicator of just how differently the Chinese and Western sides of a partnership approach business. Much of what counts for “conflict” in this book is indeed “conflict” from a Western perspective, but from the Chinese perspective, it is simply part of doing business. While Westerners are accustomed to a fair amount of conflict leading up to the signing of a contract, the general expectation is that this is the point at which conflict ends, and both parties do their best to adhere to the terms of the contract.

While it has now become practically cliché to say that Chinese and Westerners view contracts differently, Hupert opens a door on what the Chinese side is thinking both before and after contract signing, how they constantly assess the performance of both the business and their foreign partner, and how they will maneuver to improve the terms of the deal for themselves. Having this knowledge certainly will not prevent conflict, but understanding what motivates the Chinese side, and having Hupert's advice on how to address Chinese concerns (most of which they will never verbally express) will equip Western business people far better than an entire lifetime of experience in a Western-only business setting.

This 10-chapter book is structured to mirror the life of a Chinese-Western partnership from beginning to end – whether that end is a continuance of the partnership or a dissolution. In each chapter, Hupert provides clear theoretical explanations of how and why Chinese and Western expectations differ, and then he provides case studies that illustrate both successful and unsuccessful ways of dealing with conflict.

There is also a larger, fictional case study about an American partner, Stan, and a Chinese partner, Jimmy who meet in college in the US and establish a business together in Shanghai. Each chapter ends with a telling of the portion of the Stan & Jimmy story that applies to that chapter, and the story is so well-told, that the reader will find it hard to stop reading at the end of any given chapter. (In my case, I read the entire book on a flight from Los Angeles to Taipei in about three or four hours.)

I am not certain whether it was intended this way, but Hupert's new book seems to be a sort of prequel to his first book in that it is a longer and broader work covering many aspects of Chinese-foreign business partnerships, just one of which happens to be guanxi (which can be loosely translated as “connections” though there is much more to it than that). To anyone who has yet to read Guanxi for the Busy American, my advice would be to read Fragile Bridge first, then pick up Guanxi for a more in-depth treatment of this very important topic.

For those who have already read Guanxi, you will find that Fragile Bridge contains the same kind of practical advice, except that it is extended to many more situations in addition to the building of guanxi. And regardless of the order in which you read Andrew Hupert's two excellent books, if you're serious about succeeding in business (or any kind of negotiation) in China, you really cannot afford not to have both of these books in your e-reader.

Fragile Bridge: Conflict Management in Chinese Business is available for $9.99 in Kindle format at Amazon.com and in many other e-book formats at Smashwords.com.

Thursday, May 31, 2012

In praise of public-private partnership

Today's splashdown of the SpaceX Dragon capsule off the coast of California completes the first successful visit of a private spacecraft to the International Space Station.

This news isn't really China-related, but it illustrates an important aspect of state vs private sector investment. To over-generalize a bit, (American) conservatives would prefer that the private sector do everything, and (American) liberals would prefer that the state do everything.

Here we have illustrated the importance of public-private partnership. Without the initial leadership of the state, the US would not have reached the moon in 1969. It took far more investment than any private sector investor would have been willing to risk for what was basically a huge experiment with no monetary payoff.

Based on a few decades of learning, a private company has now managed to come up with a solution far less expensive, and at least as effective, as anything the state could have come up with to send supplies to the space station. And this was apparently just the beginning; the Dragon capsule will someday ferry people too.

Bringing this lesson closer to my area of interest, perhaps it also makes sense that governments subsidize the development of alternative methods of fueling personal transportation. Right now, the economics of electric vehicles simply don't make sense. This is why it is important that governments step in to subsidize the experimental phase.

As with the original moon shot, alternative fuels and methods of propulsion are experimental (and arguably far more important), but no private sector investor would be willing to take such a risk to build a product that doesn't yet provide a positive return on investment.

This isn't to say that governments will always be right, but that's the nature of experimentation. Thomas Edison conducted over 3,000 experiments with different materials for filaments until he finally made a lightbulb that worked. For small experiments such as Edison's, no government help was needed, but without government regulation and assistance, we would never have moved beyond the traditional gas guzzlers we were driving back in the 1970s.

When I began to research business-government relations in China's auto industry several years ago, I started with a question of why China seemed to be achieving such great success under the heavy hand of the state. What I have since learned is that, while, yes, the state can drive outstanding growth in an agrarian society with low living standards, the ability of the government to make good decisions declines as technology becomes more complex.

China has now reached a point where its government needs to be smart enough to step back and allow the private sector to compete freely (and not just talk about it). All the government assistance in the world will not make state-owned businesses competitive. They simply lack the proper incentives.

At the same time, the American people also need to realize that the US will never grow as fast as China has grown over the past three decades (and neither will China again). We also need to realize that there is a place for government to invest in experimentation that will result in much-needed future technology. Sometimes the government will make mistakes, but fear of making mistakes will deprive us of potential successes.

Being counted among the most advanced countries on earth is not easy, as the Chinese are about to discover, but the notion that either the government OR the private sector is best suited to drive future innovation is a false choice. We need both. We need the competitive zeal of the private sector, and, sometimes, we also need the deep pockets of the government to take on problems too big for the private sector.

The Chinese system of dominant state ownership is nearing the end of its usefulness, and if the Chinese don't figure that out, they are doomed to stagnation and chaos. US arguments over "socialism" vs "free-markets" are also pointless. Somewhere, in the middle, there is an ideal system in which ownership still lies primarily with the private sector, but the government takes the big risks that can potentially save the planet for our children and grandchildren.

This news isn't really China-related, but it illustrates an important aspect of state vs private sector investment. To over-generalize a bit, (American) conservatives would prefer that the private sector do everything, and (American) liberals would prefer that the state do everything.

Here we have illustrated the importance of public-private partnership. Without the initial leadership of the state, the US would not have reached the moon in 1969. It took far more investment than any private sector investor would have been willing to risk for what was basically a huge experiment with no monetary payoff.

Based on a few decades of learning, a private company has now managed to come up with a solution far less expensive, and at least as effective, as anything the state could have come up with to send supplies to the space station. And this was apparently just the beginning; the Dragon capsule will someday ferry people too.

Bringing this lesson closer to my area of interest, perhaps it also makes sense that governments subsidize the development of alternative methods of fueling personal transportation. Right now, the economics of electric vehicles simply don't make sense. This is why it is important that governments step in to subsidize the experimental phase.

As with the original moon shot, alternative fuels and methods of propulsion are experimental (and arguably far more important), but no private sector investor would be willing to take such a risk to build a product that doesn't yet provide a positive return on investment.

This isn't to say that governments will always be right, but that's the nature of experimentation. Thomas Edison conducted over 3,000 experiments with different materials for filaments until he finally made a lightbulb that worked. For small experiments such as Edison's, no government help was needed, but without government regulation and assistance, we would never have moved beyond the traditional gas guzzlers we were driving back in the 1970s.

|

| Scorn of conservatives: The Chevrolet Volt |

When I began to research business-government relations in China's auto industry several years ago, I started with a question of why China seemed to be achieving such great success under the heavy hand of the state. What I have since learned is that, while, yes, the state can drive outstanding growth in an agrarian society with low living standards, the ability of the government to make good decisions declines as technology becomes more complex.

China has now reached a point where its government needs to be smart enough to step back and allow the private sector to compete freely (and not just talk about it). All the government assistance in the world will not make state-owned businesses competitive. They simply lack the proper incentives.

At the same time, the American people also need to realize that the US will never grow as fast as China has grown over the past three decades (and neither will China again). We also need to realize that there is a place for government to invest in experimentation that will result in much-needed future technology. Sometimes the government will make mistakes, but fear of making mistakes will deprive us of potential successes.

Being counted among the most advanced countries on earth is not easy, as the Chinese are about to discover, but the notion that either the government OR the private sector is best suited to drive future innovation is a false choice. We need both. We need the competitive zeal of the private sector, and, sometimes, we also need the deep pockets of the government to take on problems too big for the private sector.

The Chinese system of dominant state ownership is nearing the end of its usefulness, and if the Chinese don't figure that out, they are doomed to stagnation and chaos. US arguments over "socialism" vs "free-markets" are also pointless. Somewhere, in the middle, there is an ideal system in which ownership still lies primarily with the private sector, but the government takes the big risks that can potentially save the planet for our children and grandchildren.

Friday, May 25, 2012

Book Giveaway!

To celebrate the imminent release of my book, Designated Drivers: How China Plans to Dominate the Global Auto Industry, I will be giving away three signed copies next week.

Designated Drivers is about much more than the auto industry. It uses China's auto industry to tell a story about how China's central government manages its economy in its drive to create global industrial champions. It's an important story for anyone considering doing business in or with China as well as for policymakers who want to better understand business-government relations in what is still the world's most consistently fast-growing economy.

If you would like a chance to win a free copy of my book, all you need to do is "like" the Designated Drivers Facebook page and share it on your page. The Facebook page is here:

https://www.facebook.com/DesignatedDriversChina

On Tuesday, May 29 at 08:00, pacific time, I will select three "likers" at random* and send each of them an autographed copy of Designated Drivers.

And if the number of "likes" surpasses 500, I'll throw in another two copies for a total of five possibilities to win!

This morning a friend emailed me a picture taken at a bookstore in Hong Kong showing a few copies already on the shelves there, so it should only be another week or so before copies reach North America.

_______________

* To ensure randomness, I will copy all names into an Excel spreadsheet, number them consecutively, and use Excel's random function to select three (or maybe five!) numbers from the list.

Designated Drivers is about much more than the auto industry. It uses China's auto industry to tell a story about how China's central government manages its economy in its drive to create global industrial champions. It's an important story for anyone considering doing business in or with China as well as for policymakers who want to better understand business-government relations in what is still the world's most consistently fast-growing economy.

If you would like a chance to win a free copy of my book, all you need to do is "like" the Designated Drivers Facebook page and share it on your page. The Facebook page is here:

https://www.facebook.com/DesignatedDriversChina

On Tuesday, May 29 at 08:00, pacific time, I will select three "likers" at random* and send each of them an autographed copy of Designated Drivers.

And if the number of "likes" surpasses 500, I'll throw in another two copies for a total of five possibilities to win!

This morning a friend emailed me a picture taken at a bookstore in Hong Kong showing a few copies already on the shelves there, so it should only be another week or so before copies reach North America.

_______________

* To ensure randomness, I will copy all names into an Excel spreadsheet, number them consecutively, and use Excel's random function to select three (or maybe five!) numbers from the list.

Monday, May 14, 2012

Thoughts on the 2012 Beijing Auto Show

I recently traveled to Beijing to attend the 2012 Beijing Auto Show as well as to attend the Automotive News China Conference. While no one can expect to gain a full understanding of China during a quick trip like this one (indeed, one must live there for an extended period in order to learn that he can never fully understand China), such trips are often helpful for taking the pulse of what's going on at the moment.

First, a bit about the conference. Like most industry conferences, this one is basically a big networking opportunity surrounded by presentations from industry notables. My greatest impression was that, despite less than impressive growth numbers in the first quarter of this year, everyone seemed very optimistic about the prospects for longer term growth in China's auto market.

A lot of the discussion centered around the still largely untapped markets in China's Tier-3 and Tier-4 cities, and how dealer networks have aggressive expansion plans to take advantage of burgeoning demand among middle class Chinese consumers. And because the majority of auto purchases in China are still cash transactions, dealers see the ability to expand and sell their finance offerings as another key to getting more people behind the wheel.

From a personal point-of-view, while I learned much from the presentations, also I could not help but wonder why, for all of its stated intention of doing its own thing, going its own way, doing everything with "Chinese characteristics," China seems determined to build a consumer society with "American characteristics." Why is China copying some of the least attractive of American characteristics such as streets crowded with slow-moving vehicles, polluted air and consumer debt that has allowed us to live beyond our means?

While I wouldn't want to deny China the opportunity to develop itself and to improve standards of living, I wonder why China's planners cannot look down the road and foresee the kinds of problems that already exist in the US. Here is a chance for creative thinkers to leap ahead to solutions that will allow Chinese citizens the kind of personal mobility that will enhance their lives without bringing many of their negative characteristics.

And speaking of leaping ahead, this is a good point for me insert a few pictures and observations from the Auto Show.

This first picture is of a concept car shown by Chery, a local state-owned automaker from Anhui province. Actually, it's two cars, called the @Ant, connected to each other.

While I have to give Chery kudos for its creativity on this one, I felt like their design was more of a novelty than something that could truly solve problems. First, even though these cars are intended to be smaller, their footprints are actually quite large. Because the front wheels are intended to link up with another car in front, when the car is driven solo, those extended front wheels still take up a lot of room.

Also (and I really hate to nitpick here) aren't we pretty close to having technology what would allow cars to "link up" virtually with the use of software and proximity sensors? Such wireless technology would eventually allow for linkages to take place on the fly without the vehicles even needing to slow down. I'm guessing that the physical linkage suggested by Chery would require the vehicles to slow down, if not stop altogether, in order to establish a link.

In terms of more realistic concept vehicles, my impression this time was that Chinese designers (in some cases) have improved their design skills and visions since the last auto show I attended in Shanghai in 2009.

This crossover concept, also from Chery, really flows with some clever use of side panel creasing.

And this MG concept from Shanghai Auto was also an eye-catcher. I like the way they were able to integrate the traditional MG look with the round headlights into a very contemporary design.

And here's another nice concept from First Auto Works with really smooth lines. Unfortunately, FAW had it displayed in such a way that it was nearly impossible to capture the whole car in a single photo.

As in Shanghai 2009, everyone this year was still eager to demonstrate that they were developing new energy vehicles. Also like Shanghai 2009, practically none of the green vehicles on display could actually be bought by Chinese consumers. (Of course, the foreign automakers also showed their NEV offerings like the Toyota Prius, Nissan Leaf, Chevy Volt, etc.)

Here's the apparently electric version of Guangzhou Auto's Trumpchi which is built on an older Alfa Romeo platform (no doubt acquired from its new partner Fiat which owns Alfa).

I say this is an "apparently" electric version because, like many NEVs at the show, the only indication of their NEV status was a nearby sign or decals on the side. A look at the interior of some of these cars revealed the traditional shifter associated with an automatic or manual transmission -- which electric vehicles don't need.

This is the Denza, a new brand created by a joint venture between the private Chinese firm BYD and Daimler of Germany. This NEV is slated to go on sale in 2014.

Suicide doors also seemed to be all the rage this year, though no one actually has the guts to sell a car with this really cool feature.

Another common theme I noted was the traditional Chinese blue and white pottery theme on this sedan by local Chinese automaker Hawtai and a custom version of the Smart for Two.

And in case you are still wondering why Beijing wouldn't let Sichuan Tengzhong buy Hummer a few years ago...

... here's the Chinese version made by Dongfeng Motor. As you can see it's every bit as pretentious as the old US version which (fortunately) is no longer made, depriving some Americans of opportunities to unwittingly make fools of themselves. ;-)

I didn't take a lot of photos of the non-Chinese automakers' stands as my interest on this trip was primarily in what the Chinese are working on. However, I did notice that all of the Detroit Three are projecting a lot more confidence than they did in 2009. If you remember, GM and Chrysler were still on the ropes then, and Ford was also pretty deep in debt. This year, all three had much larger stands, a lot more vehicles (including some really fascinating concepts) and were drawing such huge crowds that it was hard to walk through.

Here's a cool batmobile-looking concept from Chevrolet called the Miray.

The dancing blondes at the Ford stand attracted every red-blooded Chinese man with a point-and-shoot camera like bees to clover, so I couldn't get a good look at the new SUV Ford was displaying.

China's biggest auto show alternates between Bejing and Shanghai on even and odd years, respectively. In the future, I think the odd years will be enough for me.

First, a bit about the conference. Like most industry conferences, this one is basically a big networking opportunity surrounded by presentations from industry notables. My greatest impression was that, despite less than impressive growth numbers in the first quarter of this year, everyone seemed very optimistic about the prospects for longer term growth in China's auto market.

A lot of the discussion centered around the still largely untapped markets in China's Tier-3 and Tier-4 cities, and how dealer networks have aggressive expansion plans to take advantage of burgeoning demand among middle class Chinese consumers. And because the majority of auto purchases in China are still cash transactions, dealers see the ability to expand and sell their finance offerings as another key to getting more people behind the wheel.

From a personal point-of-view, while I learned much from the presentations, also I could not help but wonder why, for all of its stated intention of doing its own thing, going its own way, doing everything with "Chinese characteristics," China seems determined to build a consumer society with "American characteristics." Why is China copying some of the least attractive of American characteristics such as streets crowded with slow-moving vehicles, polluted air and consumer debt that has allowed us to live beyond our means?

While I wouldn't want to deny China the opportunity to develop itself and to improve standards of living, I wonder why China's planners cannot look down the road and foresee the kinds of problems that already exist in the US. Here is a chance for creative thinkers to leap ahead to solutions that will allow Chinese citizens the kind of personal mobility that will enhance their lives without bringing many of their negative characteristics.

And speaking of leaping ahead, this is a good point for me insert a few pictures and observations from the Auto Show.

This first picture is of a concept car shown by Chery, a local state-owned automaker from Anhui province. Actually, it's two cars, called the @Ant, connected to each other.

While I have to give Chery kudos for its creativity on this one, I felt like their design was more of a novelty than something that could truly solve problems. First, even though these cars are intended to be smaller, their footprints are actually quite large. Because the front wheels are intended to link up with another car in front, when the car is driven solo, those extended front wheels still take up a lot of room.

Also (and I really hate to nitpick here) aren't we pretty close to having technology what would allow cars to "link up" virtually with the use of software and proximity sensors? Such wireless technology would eventually allow for linkages to take place on the fly without the vehicles even needing to slow down. I'm guessing that the physical linkage suggested by Chery would require the vehicles to slow down, if not stop altogether, in order to establish a link.

In terms of more realistic concept vehicles, my impression this time was that Chinese designers (in some cases) have improved their design skills and visions since the last auto show I attended in Shanghai in 2009.

This crossover concept, also from Chery, really flows with some clever use of side panel creasing.

And this MG concept from Shanghai Auto was also an eye-catcher. I like the way they were able to integrate the traditional MG look with the round headlights into a very contemporary design.

And here's another nice concept from First Auto Works with really smooth lines. Unfortunately, FAW had it displayed in such a way that it was nearly impossible to capture the whole car in a single photo.

As in Shanghai 2009, everyone this year was still eager to demonstrate that they were developing new energy vehicles. Also like Shanghai 2009, practically none of the green vehicles on display could actually be bought by Chinese consumers. (Of course, the foreign automakers also showed their NEV offerings like the Toyota Prius, Nissan Leaf, Chevy Volt, etc.)

Here's the apparently electric version of Guangzhou Auto's Trumpchi which is built on an older Alfa Romeo platform (no doubt acquired from its new partner Fiat which owns Alfa).

I say this is an "apparently" electric version because, like many NEVs at the show, the only indication of their NEV status was a nearby sign or decals on the side. A look at the interior of some of these cars revealed the traditional shifter associated with an automatic or manual transmission -- which electric vehicles don't need.

This is the Denza, a new brand created by a joint venture between the private Chinese firm BYD and Daimler of Germany. This NEV is slated to go on sale in 2014.

Suicide doors also seemed to be all the rage this year, though no one actually has the guts to sell a car with this really cool feature.

Another common theme I noted was the traditional Chinese blue and white pottery theme on this sedan by local Chinese automaker Hawtai and a custom version of the Smart for Two.

And in case you are still wondering why Beijing wouldn't let Sichuan Tengzhong buy Hummer a few years ago...

... here's the Chinese version made by Dongfeng Motor. As you can see it's every bit as pretentious as the old US version which (fortunately) is no longer made, depriving some Americans of opportunities to unwittingly make fools of themselves. ;-)

I didn't take a lot of photos of the non-Chinese automakers' stands as my interest on this trip was primarily in what the Chinese are working on. However, I did notice that all of the Detroit Three are projecting a lot more confidence than they did in 2009. If you remember, GM and Chrysler were still on the ropes then, and Ford was also pretty deep in debt. This year, all three had much larger stands, a lot more vehicles (including some really fascinating concepts) and were drawing such huge crowds that it was hard to walk through.

Here's a cool batmobile-looking concept from Chevrolet called the Miray.

The dancing blondes at the Ford stand attracted every red-blooded Chinese man with a point-and-shoot camera like bees to clover, so I couldn't get a good look at the new SUV Ford was displaying.

And finally, here's a shot of an Audi stand outside of one of the pavilions. What's so interesting about this? The characters on the building are inviting people to check out their used cars (二手车, literally "second hand car").

China's auto market is still so new that about 85% of car buyers today are still first-time buyers. But since 2005 over 80 million vehicles have been sold in China. This means that an increasing number of used vehicles will be available as many previous first-time buyers trade up.

I would not have expected to see used cars being touted at an auto show, but since Chinese consumers still overwhelmingly consider foreign brands to be superior to Chinese brands, it makes sense that a first-time buyer might be persuaded to buy a used car, certified by a foreign automaker, rather than a brand new Chinese-branded car.

As for the auto show itself, I have to say that it was a bit of a disappointment. The organizers of this show appeared to be more interested in how many tickets they could sell than in putting on a good show. Even though they designated different days as media days, industry days and public days, there appeared to be no real distinction as tickets were offered for sale to anyone who showed up.

Wednesday, April 18, 2012

GM is getting its 1% back, and it won't be cheap

Back in January, GM announced it wanted to buy back the 1% it had sold to its partner, Shanghai Auto (SAIC). In the post I wrote at that time, here was my prediction:

As it turns out, this is exactly what is happening. According to an article (free registration required) from Automotive News China:

As for the ongoing implications, GM once again presumably has an equal say in SAIC-GM board meetings. This is good for GM because they will have leverage in charting the direction of the firm, appointing executives, and planning production.

However, this new sales organization, of which SAIC will now own 51%, will funnel a bit more cash toward SAIC for the foreseeable future. What's that worth? According to my very rough, back-of-the-envelope math, possibly as much as $150 million a year in sales -- that's every year in perpetuity.*

If my math is even close to correct -- cut my figure in half and assume $75 million a year in sales -- that will very quickly add up to a lot more than the $85 million or so GM originally got for selling that 1% to SAIC in 2009.

Of course, SAIC and GM could just tell us what this will cost and people like me wouldn't have to do voodoo math. I'm sure GM's shareholders would like to know.

The only way I can see this happening is if GM were to agree to set up the sales organization that SAIC had first proposed, which may be possible now that the US government is no longer a majority owner in GM (though still technically the controlling owner).

As it turns out, this is exactly what is happening. According to an article (free registration required) from Automotive News China:

Company CEO Dan Akerson told the Journal that the partners plan to split Shanghai GM into two units: sales and operations.The remaining question, which the partners have not yet answered, is what consideration is changing hands. How much is GM paying to SAIC for the 1% of the manufacturing operation?

General Motors would have a 50 percent share of the operations unit, which would make product decisions. SAIC would retain a 51 percent share of the sales unit, which would allow the Chinese automaker to book the joint venture's revenue.

As for the ongoing implications, GM once again presumably has an equal say in SAIC-GM board meetings. This is good for GM because they will have leverage in charting the direction of the firm, appointing executives, and planning production.

However, this new sales organization, of which SAIC will now own 51%, will funnel a bit more cash toward SAIC for the foreseeable future. What's that worth? According to my very rough, back-of-the-envelope math, possibly as much as $150 million a year in sales -- that's every year in perpetuity.*

If my math is even close to correct -- cut my figure in half and assume $75 million a year in sales -- that will very quickly add up to a lot more than the $85 million or so GM originally got for selling that 1% to SAIC in 2009.

Of course, SAIC and GM could just tell us what this will cost and people like me wouldn't have to do voodoo math. I'm sure GM's shareholders would like to know.

___________________________

* My back-of-the-envelope math. According to the WSJ, GM gets about $30 billion in revenue a year from China. Last year, SAIC-GM sold 1.2 million vehicles and SAIC-GM-Wuling sold 1.3 million (data here). Again, very roughly, taking GM's 49% of SAIC-GM and GM's 44% of SAIC-GM-Wuling reveals that about 52% of GM's China revenue came from SAIC-GM. Even more roughly, 52% of GM's $30 billion is $15.6 billion and 1% of that is $156 million.

Thursday, April 5, 2012

Wen Jiabao gets it, but no one cares

On Tuesday (3 April 2012) major media outlets reported that Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao was getting ready to take on China's giant state-owned banks. He was quoted in an article in the Wall Street Journal:

Setting aside the fact that there are too many banks in China for any one to have a monopoly (let us not forget that the "mono" part of monopoly means "one") Wen's criticism was definitely warranted. China's top five banks account for more than 55 percent of loans in China's banking system.

Setting aside the fact that there are too many banks in China for any one to have a monopoly (let us not forget that the "mono" part of monopoly means "one") Wen's criticism was definitely warranted. China's top five banks account for more than 55 percent of loans in China's banking system.

On Tuesday I posted this WSJ article on Facebook and offered the comment that, "what Wen really means is that the dominance of the big state-owned banks needs to be broken so that privately owned banks are better able to compete for lending business. There are plenty of banks in China. The problem is that the biggest are state-owned and are managed according to political, not economic, principles."

But that isn't the whole problem. The other part of the problem is that, as long as China's major industrial firms are also state-owned, they will be considered by bankers to be a better credit risk than private firms, and they will absorb most of the funds available for lending.

It isn't that private firms are necessarily a poor credit risk. Indeed, some (possibly most) private firms are better managed than state-owned enterprises (SOEs), but unlike the SOEs, the private firms aren't backed by the full faith and credit of the central government. Consequently, China's private sector continues to be starved of funding.

On Thursday (5 April 2012), George Chen of the South China Morning Post wrote an article entitled "Bankers Reject Wen's Criticism." (Sorry, SCMP is behind a paywall.) Some of the quotes in this article are simply golden. It's almost as if China's bankers wanted to help me make my argument. One unnamed senior bank executive was quoted:

What I find strange about this response from a senior banker is that he apparently does not associate Wen Jiabao with "the government" -- which is odd since the Premier's job description is "Head of Government."

What this tells us is, first, that Wen Jiabao's views, if they were ever considered to carry any weight, are no longer deemed worthy of respect. Even though he'll be Premier until next March, in the eyes of many, he's already a lame duck.

Second, if the Premier isn't calling the shots, then someone else -- whoever this senior banker considers to be "the government" -- is calling the shots. And whoever that is (and I'm sure it's a faction of the senior leadership) is still not interested in opening up China's industries to free and fair competition from the private sector.

In my forthcoming book, I make what I believe to be a very strong case for the fact that China's insistence on state dominance of its major industries is stifling the country's innovative capabilities. This latest episode with the banks just further confirms my belief that the powers that matter have yet to see a connection between state dominance and China's continued reliance on copying of foreign technology rather than development of its own.

Wen Jiabao gets it, but he already has one foot out the door.

Let me be frank. Our banks earn profit too easily. Why? Because a small number of large banks have a monopoly...To break the monopoly we must allow private capital to flow into the finance sector.

Setting aside the fact that there are too many banks in China for any one to have a monopoly (let us not forget that the "mono" part of monopoly means "one") Wen's criticism was definitely warranted. China's top five banks account for more than 55 percent of loans in China's banking system.

Setting aside the fact that there are too many banks in China for any one to have a monopoly (let us not forget that the "mono" part of monopoly means "one") Wen's criticism was definitely warranted. China's top five banks account for more than 55 percent of loans in China's banking system.On Tuesday I posted this WSJ article on Facebook and offered the comment that, "what Wen really means is that the dominance of the big state-owned banks needs to be broken so that privately owned banks are better able to compete for lending business. There are plenty of banks in China. The problem is that the biggest are state-owned and are managed according to political, not economic, principles."

But that isn't the whole problem. The other part of the problem is that, as long as China's major industrial firms are also state-owned, they will be considered by bankers to be a better credit risk than private firms, and they will absorb most of the funds available for lending.

It isn't that private firms are necessarily a poor credit risk. Indeed, some (possibly most) private firms are better managed than state-owned enterprises (SOEs), but unlike the SOEs, the private firms aren't backed by the full faith and credit of the central government. Consequently, China's private sector continues to be starved of funding.

On Thursday (5 April 2012), George Chen of the South China Morning Post wrote an article entitled "Bankers Reject Wen's Criticism." (Sorry, SCMP is behind a paywall.) Some of the quotes in this article are simply golden. It's almost as if China's bankers wanted to help me make my argument. One unnamed senior bank executive was quoted:

I don't think it [Wen's comment] is a fair comment. Because we're a state-owned bank, much of our business and loans are to support whatever the government needs, for example to support the growth of many state-owned enterprises. We must listen to the government, which already gives us a lot of orders and guidelines.Right there you have an explicit admission that "the government" wants the banks to support the SOEs. Of course, we already knew that, but it's nice occasionally to have insiders admit as much.

What I find strange about this response from a senior banker is that he apparently does not associate Wen Jiabao with "the government" -- which is odd since the Premier's job description is "Head of Government."

What this tells us is, first, that Wen Jiabao's views, if they were ever considered to carry any weight, are no longer deemed worthy of respect. Even though he'll be Premier until next March, in the eyes of many, he's already a lame duck.

Second, if the Premier isn't calling the shots, then someone else -- whoever this senior banker considers to be "the government" -- is calling the shots. And whoever that is (and I'm sure it's a faction of the senior leadership) is still not interested in opening up China's industries to free and fair competition from the private sector.

In my forthcoming book, I make what I believe to be a very strong case for the fact that China's insistence on state dominance of its major industries is stifling the country's innovative capabilities. This latest episode with the banks just further confirms my belief that the powers that matter have yet to see a connection between state dominance and China's continued reliance on copying of foreign technology rather than development of its own.

Wen Jiabao gets it, but he already has one foot out the door.

Thursday, March 29, 2012

Part of me is on Facebook now

Long-time followers of this blog may have noted that I don't post as often as I did during 2009, my first year of blogging. There are a couple of reasons for this.

First, once I set about writing my dissertation in 2010, I would spend entire days writing, so it became difficult also to take the time to write blog posts. Now that I am working, I still find it hard to post more than 2-3 times a month, but I will continue to post here when I identify issues that deserve more analysis than is provided in the mainstream media.

Secondly, my increased use of Facebook allows me to make shorter commentaries on news stories that don't necessarily merit a longer blog post. If this is something that also interests you, please "like" the Facebook page for my book, Designated Drivers, which you can find here.*

On that page I comment mostly on China's auto industry, but also on general business/government issues in China. Also, please feel free to jump in and comment as well, either here or on the Facebook page. This is all about making each other smarter, so I welcome comments and criticism.

_______________________

* Sorry, but I really hate the term "like" that Facebook insists on using. If you prefer, think of it as "following" instead. You can be interested in what I have to say without necessarily liking it. :)

First, once I set about writing my dissertation in 2010, I would spend entire days writing, so it became difficult also to take the time to write blog posts. Now that I am working, I still find it hard to post more than 2-3 times a month, but I will continue to post here when I identify issues that deserve more analysis than is provided in the mainstream media.

Secondly, my increased use of Facebook allows me to make shorter commentaries on news stories that don't necessarily merit a longer blog post. If this is something that also interests you, please "like" the Facebook page for my book, Designated Drivers, which you can find here.*

On that page I comment mostly on China's auto industry, but also on general business/government issues in China. Also, please feel free to jump in and comment as well, either here or on the Facebook page. This is all about making each other smarter, so I welcome comments and criticism.

_______________________

* Sorry, but I really hate the term "like" that Facebook insists on using. If you prefer, think of it as "following" instead. You can be interested in what I have to say without necessarily liking it. :)

Wednesday, March 28, 2012

Is GM handing China another win?

General Motors announced today that it has signed a memorandum of understanding with the China Automotive Technology and Research Center (CATARC) in which CATARC will reportedly...

Since part of GM's purpose is to gain influence over policymakers, this relationship with an organization that is part of the central government cannot hurt. But there is more to CATARC than meets the eye.

Not only is CATARC an auto industry regulator that is essentially owned by the central government, but it is also a competitor of GM's through its ownership in the Tianjin Qingyuan Electric Vehicle Company (Qingyuan). According to Qingyuan's website, the company both develops and produces clean energy vehicles and components, which sounds remarkably like something that GM does.

Qingyuan's "principal shareholder" is CATARC, and another of Qingyuan's shareholders is the Tianjin Lishen Battery Company, a producer of lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles, which is, of course a competitor of LG Chem, the manufacturer of the battery in the Chevrolet Volt. (Lishen, incidentally, makes the li-ion battery for the Coda electric car.)

So what does all of this mean? Am I saying that GM has handed its intellectual property over to CATARC so they may copy at will? Not exactly. CATARC, after all, also has a reputation to protect, so I am doubtful that they would so blatantly copy GM's Volt technology. But how certain can GM be that its technology will not find its way, through CATARC, into the hands of Qingyuan, or Lishen, or any of the dozens of Chinese automakers who bring their cars to CATARC for testing?

GM is no stranger to having its IP copied in China. Back in 2003, GM discovered that Chery had somehow obtained the plans to the Chevrolet Spark, and used them to develop the QQ which Chery got to market several months ahead of the Spark. And when GM went to its partner, Shanghai Auto, to complain about this miscreant that had been copying its technology, only then did GM learn that Shanghai Auto was also a part owner of Chery. (Long story short, GM sued, then settled out of court with Chery, which admitted no wrongdoing, and Shanghai Auto got rid of its shares in Chery.)

In all honesty, I find it hard to blame Chinese automakers for copying foreign technology and designs. After all, this is what all developing countries do when they are trying to catch up. All developed countries -- including the US -- at one time or another, copied other countries' technologies with reckless abandon.

I do, however, blame foreign automakers (and manufacturers in pretty much any industry) for sometimes naively risking their shareholders' valuable IP for a share of the Chinese market. The goal of the Chinese automakers is to win -- as it should be. But foreign automakers need to understand that the ultimate goal of China's automakers is to no longer need them. When Chinese partners say their aim is for a "win-win," this means they get to win twice.*

___________________

* I don't know for certain whether I was the first person to say this about the concept of "win-win", but I had not heard it before I tweeted it from my hotel room in Shanghai in January of 2010 (as documented by @rudenoon on his blog). :)

...manage GM’s fleet of demonstration Volts and will assist GM China in meeting certain objectives.Who is CATARC? From their English website:

These [objectives] will include gaining the support of key decision makers crafting vehicle electrification policy in China.

China Automotive Technology and Research Center (CATARC) was established in 1985 response to the need of the state for the management of auto industry and upon the approval of the China National Science and Technology Commission. It is now affiliated to SASAC.CATARC is "affiliated to SASAC" (State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission) which is essentially the organization that holds the shares of central state-owned enterprises. CATARC is also a major regulatory organization in that all automobiles need to be tested by CATARC before they may be certified for the road in China.

As a technical administration body in the auto industry and a technical support organization to the governmental authorities, CATARC assists the government in such activities as auto standard and technical regulation formulating, product certification testing, quality system certification, industry planning and policy research, information service and common technology research.

Since part of GM's purpose is to gain influence over policymakers, this relationship with an organization that is part of the central government cannot hurt. But there is more to CATARC than meets the eye.

Not only is CATARC an auto industry regulator that is essentially owned by the central government, but it is also a competitor of GM's through its ownership in the Tianjin Qingyuan Electric Vehicle Company (Qingyuan). According to Qingyuan's website, the company both develops and produces clean energy vehicles and components, which sounds remarkably like something that GM does.

Qingyuan's "principal shareholder" is CATARC, and another of Qingyuan's shareholders is the Tianjin Lishen Battery Company, a producer of lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles, which is, of course a competitor of LG Chem, the manufacturer of the battery in the Chevrolet Volt. (Lishen, incidentally, makes the li-ion battery for the Coda electric car.)

So what does all of this mean? Am I saying that GM has handed its intellectual property over to CATARC so they may copy at will? Not exactly. CATARC, after all, also has a reputation to protect, so I am doubtful that they would so blatantly copy GM's Volt technology. But how certain can GM be that its technology will not find its way, through CATARC, into the hands of Qingyuan, or Lishen, or any of the dozens of Chinese automakers who bring their cars to CATARC for testing?

GM is no stranger to having its IP copied in China. Back in 2003, GM discovered that Chery had somehow obtained the plans to the Chevrolet Spark, and used them to develop the QQ which Chery got to market several months ahead of the Spark. And when GM went to its partner, Shanghai Auto, to complain about this miscreant that had been copying its technology, only then did GM learn that Shanghai Auto was also a part owner of Chery. (Long story short, GM sued, then settled out of court with Chery, which admitted no wrongdoing, and Shanghai Auto got rid of its shares in Chery.)

In all honesty, I find it hard to blame Chinese automakers for copying foreign technology and designs. After all, this is what all developing countries do when they are trying to catch up. All developed countries -- including the US -- at one time or another, copied other countries' technologies with reckless abandon.

I do, however, blame foreign automakers (and manufacturers in pretty much any industry) for sometimes naively risking their shareholders' valuable IP for a share of the Chinese market. The goal of the Chinese automakers is to win -- as it should be. But foreign automakers need to understand that the ultimate goal of China's automakers is to no longer need them. When Chinese partners say their aim is for a "win-win," this means they get to win twice.*

___________________

* I don't know for certain whether I was the first person to say this about the concept of "win-win", but I had not heard it before I tweeted it from my hotel room in Shanghai in January of 2010 (as documented by @rudenoon on his blog). :)

Friday, March 23, 2012

Time for a Shakeout in China's Auto Industry?

Yesterday China Bureau Chief of Automotive News, Yang Jian posted an interesting article (free registration reqd.) speculating as to possible consequences of a recent slowdown in auto sales in China. In the first two months of 2012, auto sales decreased four percent, year-on-year – and this comes on the heels of (for China) a rather anemic 2011 in which sales only grew about 2.5% and Chinese-branded passenger vehicles gave up nearly two percentage points in market share to the foreign brands.

In short, Yang Jian's point is that, should this drop in sales become a trend that lasts through 2012, some of the weaker players in China's auto industry could be forced into bankruptcy or possibly out of business altogether.

From the perspective of China's central government, which has been begging and pleading for this heavily fragmented industry to consolidate itself for nearly three decades, this wouldn't be such a bad thing. (Of course it would be a bad thing for the employees of those companies that went out of business.) There are still well over 100 vehicle manufacturers operating in China (compared to only 24 in the United States), and this fragmentation prevents the industry as a whole from becoming more competitive vis-à-vis the foreign automakers.

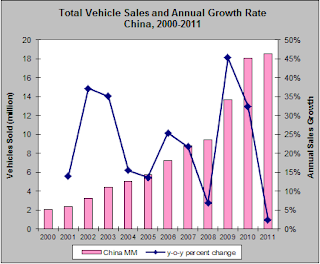

So what is the likelihood that a decline in sales could lead to a shakeout of the weaker players? Well, let's take a look at what happened the last time China's auto industry experienced a slowdown in sales growth. After enjoying annual sales growth of anywhere between 14% and 37% since 2001, the onset of the Great Recession in 2008 caused China's growth rate to drop to a horrifyingly low 7%. (Yes, the word “horrifyingly” should be interpreted sarcastically.)

I remember talking to a lot of auto industry insiders in China in the spring of 2009 when some of them lamented the fact that the much hoped-for shakeout didn't happen back then. (And it seems like Yang Jian himself may have been among those who expressed such sentiment to me then.)

Why didn't the shakeout happen?

The central government rode to the rescue with a far-reaching stimulus program that not only prevented another year of miserably low sales growth, but that, for the first time ever, launched China into position as the world's single largest market for automobiles in 2009. Hence the lamentations from some of my interviewees at the time. As Yang Jian hopes today, many of them also hoped soft sales growth would kill off some of the weaker players in 2009.

So will the central government ride to the rescue again this year?

I think it is less likely. With large cities in China already limiting the number of cars that can be sold and driven on their streets, and with the central government clamping down on overcapacity in the industry, AND now that China is already the number one auto market in the world (they can't go any higher), a rescue is probably not in the cards.

Does that mean a shakeout will occur?

I wouldn't bet on that either. Among the top-10 automakers, Chang'an, Chery and BYD each experienced sales declines in 2011, which doesn't look good for them. Except that Chang'an is among China's “Big 4” and Chery is among China's “Small 4.” What this means is that the central government has designated these automakers to be among those remaining after the industry consolidates. And BYD is privately-owned (its shares are traded in Hong Kong), and, though it hasn't sold as many EVs and hybrids as it had hoped to by now, it is probably China's best chance of having an automaker who can compete in this space.

Will a shakeout then occur among the dozens of tiny, inefficient and unprofitable automakers scattered around the country?

I think this is the best hope, but whether the downturn will be deep enough and long enough to outlast local governments' ability to prop up these firms remains to be seen. Local governments tend to be rather fond of their automakers -- even the ones that lose money.

In short, Yang Jian's point is that, should this drop in sales become a trend that lasts through 2012, some of the weaker players in China's auto industry could be forced into bankruptcy or possibly out of business altogether.

From the perspective of China's central government, which has been begging and pleading for this heavily fragmented industry to consolidate itself for nearly three decades, this wouldn't be such a bad thing. (Of course it would be a bad thing for the employees of those companies that went out of business.) There are still well over 100 vehicle manufacturers operating in China (compared to only 24 in the United States), and this fragmentation prevents the industry as a whole from becoming more competitive vis-à-vis the foreign automakers.

So what is the likelihood that a decline in sales could lead to a shakeout of the weaker players? Well, let's take a look at what happened the last time China's auto industry experienced a slowdown in sales growth. After enjoying annual sales growth of anywhere between 14% and 37% since 2001, the onset of the Great Recession in 2008 caused China's growth rate to drop to a horrifyingly low 7%. (Yes, the word “horrifyingly” should be interpreted sarcastically.)

I remember talking to a lot of auto industry insiders in China in the spring of 2009 when some of them lamented the fact that the much hoped-for shakeout didn't happen back then. (And it seems like Yang Jian himself may have been among those who expressed such sentiment to me then.)

Why didn't the shakeout happen?

The central government rode to the rescue with a far-reaching stimulus program that not only prevented another year of miserably low sales growth, but that, for the first time ever, launched China into position as the world's single largest market for automobiles in 2009. Hence the lamentations from some of my interviewees at the time. As Yang Jian hopes today, many of them also hoped soft sales growth would kill off some of the weaker players in 2009.

So will the central government ride to the rescue again this year?

I think it is less likely. With large cities in China already limiting the number of cars that can be sold and driven on their streets, and with the central government clamping down on overcapacity in the industry, AND now that China is already the number one auto market in the world (they can't go any higher), a rescue is probably not in the cards.

Does that mean a shakeout will occur?

I wouldn't bet on that either. Among the top-10 automakers, Chang'an, Chery and BYD each experienced sales declines in 2011, which doesn't look good for them. Except that Chang'an is among China's “Big 4” and Chery is among China's “Small 4.” What this means is that the central government has designated these automakers to be among those remaining after the industry consolidates. And BYD is privately-owned (its shares are traded in Hong Kong), and, though it hasn't sold as many EVs and hybrids as it had hoped to by now, it is probably China's best chance of having an automaker who can compete in this space.

Will a shakeout then occur among the dozens of tiny, inefficient and unprofitable automakers scattered around the country?

I think this is the best hope, but whether the downturn will be deep enough and long enough to outlast local governments' ability to prop up these firms remains to be seen. Local governments tend to be rather fond of their automakers -- even the ones that lose money.

Tuesday, March 20, 2012

Andrew Hupert's "Guanxi for the Busy American"

My friend Andrew Hupert, whom I first met in Shanghai several years ago, has for years managed a couple of very practical and helpful blogs on negotiating and managing in China (ChineseNegotiation.com and ChinaSolved.com). Even before I met Andrew, I always wondered why he would give away such valuable information for free.

Well, now he's finally selling part of his wisdom in an e-book entitled Guanxi for the Busy American available at Smashwords in ten different formats including Kindle, ePub and PDF. And at a price of only $2.99, it's a bit of a steal. (Seriously, Andrew, you should charge more.)

Because it's in an e-format, it's easy to keep on pretty much any device and peruse on the plane on the way to China. And whether someone is completely new to China, or an old China hand, the book is equally useful as both a source of necessary learning, or a reminder of how things work in China.

Much of this stuff simply doesn't come naturally to Westerners, and, even after nearly 20 years of travel to China, I occasionally need reminders. The book is a relatively quick and easy read -- it took me a little over an hour -- but it's packed with both theory and practice on what this mysterious guanxi thing is all about and how to navigate one's way through a potentially tricky maze of gestures and obligations.

Andrew's writing style is clean and straightforward, but also descriptive and, at times, humorous. Among the gems are statements like "Guanxi is the sweet candy shell that coats some potentially bitter medicine." What he explains is that, while the whole process of building guanxi can seem light and even fun, it is a process that the Chinese take very seriously. Mistakes made during this process can sink a partnership before it even gets off the ground.

Among the behaviors he warns against are denigrating the value of guanxi among your Chinese hosts by saying something like, "oh yeah, we have that concept in America too: it's not what you know but who you know," which is likely to be taken as an insult. Your Chinese hosts will be more flattered if you simply admit that the whole concept baffles you and that America has nothing like it. Even if that isn't true (and if you've read this book, it won't be true) it will buy you some credit with your hosts. (I mention this particular bit of advice because I know I have violated it several times in the past.)

The book also offers a way to "de-code" some of the guanxi talk you are likely to hear at an early guanxi-building session with your hosts.

One final point (among many dozens more) is that foreigners in China need to understand that their hosts generally want very much to invest in a long term relationship. But one shouldn't be fooled into thinking that a relationship that begins well will result in an eternal bond. The Chinese simply do not see it that way. The relationship will only last as long as the Chinese partner thinks he is deriving value equal to or greater than yours. Once that calculation changes, expect a re-negotiation. And if you aren't open to re-negotiation, expect your counterpart who has invested time in learning the names of your spouse, children and pets to lose interest and stop returning your calls.

The only real criticism I can think of is regarding the title. I am not so sure that North American and Western European cultures are so different that this book wouldn't be immediately useful on both sides of the Atlantic (and down under as well). Perhaps it might have been better titled Guanxi for the Busy Westerner.

Either way, people who do business in China need to load this book onto their Kindles and iPads. And if you find yourself sending a newbie to China on behalf of your company, be sure he or she has this book ahead of time. They will need to read it several times before getting on the plane, and probably several more while they are in China.

Well, now he's finally selling part of his wisdom in an e-book entitled Guanxi for the Busy American available at Smashwords in ten different formats including Kindle, ePub and PDF. And at a price of only $2.99, it's a bit of a steal. (Seriously, Andrew, you should charge more.)

Because it's in an e-format, it's easy to keep on pretty much any device and peruse on the plane on the way to China. And whether someone is completely new to China, or an old China hand, the book is equally useful as both a source of necessary learning, or a reminder of how things work in China.

Much of this stuff simply doesn't come naturally to Westerners, and, even after nearly 20 years of travel to China, I occasionally need reminders. The book is a relatively quick and easy read -- it took me a little over an hour -- but it's packed with both theory and practice on what this mysterious guanxi thing is all about and how to navigate one's way through a potentially tricky maze of gestures and obligations.

Andrew's writing style is clean and straightforward, but also descriptive and, at times, humorous. Among the gems are statements like "Guanxi is the sweet candy shell that coats some potentially bitter medicine." What he explains is that, while the whole process of building guanxi can seem light and even fun, it is a process that the Chinese take very seriously. Mistakes made during this process can sink a partnership before it even gets off the ground.

Among the behaviors he warns against are denigrating the value of guanxi among your Chinese hosts by saying something like, "oh yeah, we have that concept in America too: it's not what you know but who you know," which is likely to be taken as an insult. Your Chinese hosts will be more flattered if you simply admit that the whole concept baffles you and that America has nothing like it. Even if that isn't true (and if you've read this book, it won't be true) it will buy you some credit with your hosts. (I mention this particular bit of advice because I know I have violated it several times in the past.)

The book also offers a way to "de-code" some of the guanxi talk you are likely to hear at an early guanxi-building session with your hosts.

When they ask if you have been to China before, they want to know if you already have connections or are likely to grant them exclusive control (over your venture).And another